History of the book

Before the book, as we know it, writing was recorded onto clay tablets and papyrus scrolls. The Library has a cuneiform tablet from 2050 BC that shows one of the earliest writing scripts developed by the ancient culture of Sumer, in the region of modern-day Iraq.

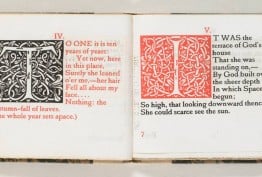

The codex form of the book, which is the one we are familiar with, was developed by the Romans around the 2nd century AD. Our collection of medieval manuscripts provides examples of the development of the book prior to printing, when scribes meticulously copied texts by hand, and they were often illuminated with gold and painted miniatures.

Johann Gutenberg’s development of the printing press in Mainz, Germany, in the 1450s revolutionised book production in Europe. We have many fine examples of books printed before 1500, such as the Nuremberg Chronicle, and the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, a work renowned for the beauty of its typography. We also have one of the largest collections of rare English printed works dating from the 15th to 18th centuries in the Emmerson collection.

Throughout their history, books have transmitted to us the great works of literature such as Shakespeare’s plays and the significant ideas of thinkers such as Charles Darwin and Germaine Greer, and they have helped us to understand the world we live in.

Through time, books have changed in look and design. In the late 19th century, the private press movement took its inspiration from the design of early printed books. More recently, artists have used the book as a vehicle for their work, as can be seen in our recent acquisition, La fin du monde. Printed in 1919, this masterpiece of image and typography is illustrated by the French Cubist Fernand Léger.

In a world filled with electronic information, books continue to survive and flourish.